|

The outpouring of anger and frustration in the present period is understandable, and necessary. It provides a sense of solidarity that, one hopes, will help people for the long march through the institutions that lies ahead.

The success of the right is not new, nor is it particularly American. We need to understand why that is. To blame it on xenophobia, racism, sexism or any other ism is insufficient. Why are people voting against their economic interests? Why are people voting against government programs that often serve them, their neighbors and their children? Why are people enthralled with the visible display of wealth rather than considering it morally repugnant?

The answer to all these questions requires more than demonstrations, whatever the number of those marching. The fact is that Trump did get elected. He campaigned in states where the electoral college votes he needed were to be found. That Hillary Clinton got two plus million votes more than he doesn’t tell us anything, especially when we consider the fact that conservative Republicans have been winning elections all over the country for the last dozen or more years. They now control both houses of Congress, and a large majority of state legislatures and governorships. And there’s no discrepancy in these between popular vote and election result. My major point: the "movements" haven't deeply rooted themselves in the constituencies for which they claim to speak. At its heart, that requires building human relationships, one-by-one; listening to people and their interests rather than "educating" them about how they should think; fostering relationships that bridge historic lines of division among "the people", rather than creating ever-increasing silos of particular interests (each legitimate in its own right) that use invidious distinction to separate themselves from others--particularly with the foundations or wealthy patrons upon whom they depend for their financing. Membership-based fundraising because nothing has more debilitated promising movements and organizations than dependence upon foundation, corporate and government funding for their core organizational budgets. The means for accomplishing this kind of fundraising are well known. In fact, their use can contribute to solidarity and organization building. Contrast this with the self-perpetuating board of directors non-profit that has a narrow agenda and its own particular patrons which it jealously guards against encroachment by other, similarly constituted, “community-based nonprofits”! We need multi-issue organizations that are membership based. Multi-issue because different people experience different problems at different times in their lives. The way relationships are initially formed is when they negotiate how to support each other in relatively small, but important to them, issues that aren’t important to others. These are called “you scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours” deals. As solidarity forms among diverse groups it is possible to join in larger, and longer-term, campaigns that address issues more deeply embedded in the status quo. All that is proposed here can be framed in a small “d” democratic language that is the language of a MAJORITY of Americans. It is a strategy for reversing the present dangerous times in which we live.

0 Comments

In the article, “Trump, Brexit--The West in Crisis” (in “Symposium/America After Trump,” Democracy--A Journal of Ideas, Winter 2017, No. 43), Ed Milliband, defeated British Labor Party candidate for Prime Minister, likens the Brexit vote to the Trump vote, and puts both in an international context of failure by progressives to offer a meaningful challenge to neoliberalism. In his words:

Wherever we are, we should learn from and not deride the insurgents from the left who are attempting to build a new participatory politics. The crisis for social democratic and center-left parties is partly one of its base: a working class no longer tied to it by tradition and by unions. The only alternative is to rebuild the base with a different form of politics—organized in and mobilizing communities. Just as we need an answer on economics and politics, so too on nationhood. If there is one area where the left has been truly left behind, it is this. The appeal to belonging is all the more potent when people have such a strong sense that power and control have left them, their communities, and their country. We see it in the allure of the Leave campaign’s slogan “Take Back Control” and, in its own way, in “Make America Great Again.” This is the hardest nut to crack, but unless we present a vision of who we are—a story of us—to our own public and the world that is consistent, believable, and attractive, we will struggle. If we are not on this pitch, then the right clearly will be—at worst, presenting an anti-immigrant, race-based, xenophobic, narrow-minded view of who we are. But what is our alternative? It must somehow be about combining a sense of fairness at home with relative openness to the world. A globalization narrative that emphasized the latter but seemed too often to forget about the former won’t do. We must be the people who combine both and see them as mutually reinforcing. And the former must precede the latter; otherwise, we are reduced to being technocrats or worse. This combination of economic fairness, political change, and national vision is a tough combination to get right. But they are the fundamentals of answering the world after Brexit and Trump. Here’s what I think is striking about what is quoted. Note, first, this point: “a working class no longer tied to it by tradition and by unions. The only alternative is to rebuild the base with a different form of politics—organized in and mobilizing communities… The appeal to belonging is all the more potent when people have such a strong sense that power and control have left them, their communities, and their country.” Then note this huge leap: “We” [progressives must] “present a vision of who we are…to our own public…It must [combine] a sense of fairness at home with relative openness to the world…This combination…[is fundamental to] answering the world after Brexit and Trump.” First, Milliband tells us (I believe with a good deal of accuracy) that tradition and unions are dying or dead, and that we have to rebuild the base (the job of labor and community organizers) because that’s important for “the appeal to belonging” which is now captured by the right because people have a sense of powerlessness (again an accurate observation). But Milliband then tells us that “we” must present to these powerless people a vision that combines fairness and openness. Who is the “we”? Politicians? Advocates? Intellectuals? Media? His own analysis tells us that none of these, nor anyone else you might add to the list, can accomplish what needs doing. That requires that the people who are now voting for the right as an expression of their powerlessness must claim power so that they can act on the best of their values and an understanding of their interests that evolves from the conversation that takes place in democratically constituted organizations. How is that power claimed? The answer is simple, though its realization is not easy: organization. People power organizations, in addition to whatever specific accomplish-ments they achieve in the world—i.e. material benefits—are the vehicles in which participants realize themselves as citizens, agents who can act in the world on their own behalf. Milliband, on the other hand, seems to think progressives just need to do a better sales job. Writing in the Arab Studies Journal, Gilbert Achcar offers a moving reflection on the meaning and tragedy of Arab Spring. His views echo those of many who participated in defeated revolutions or major reform movements—whether violent or nonviolent—of the post-World War 2 era. In reflecting on the Arab experience, Achcar says, and I quote him at length:

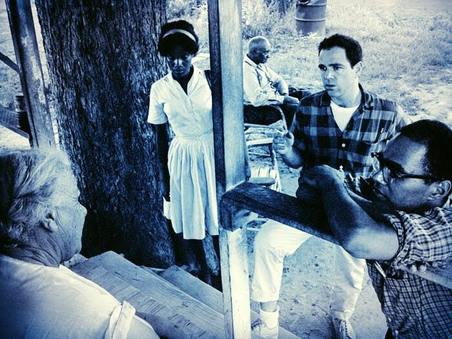

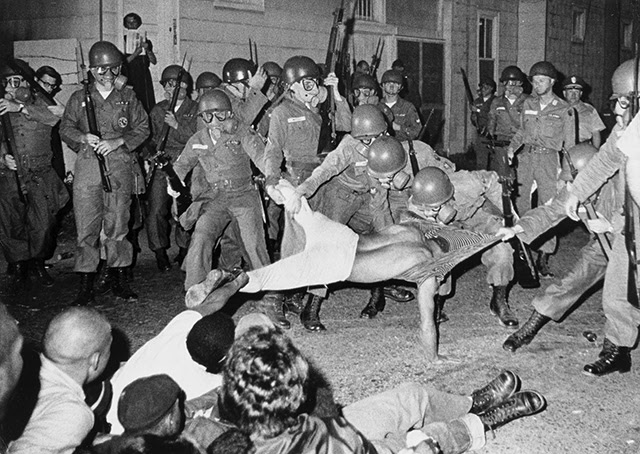

"The tragedy is that this wave of protests did not bring the renewal that was promised by the branding phrase 'Arab Spring,' but rather what followed were more of the old calamities, aggravated to a frightening degree in some cases. It is necessary therefore to emphasize two crucial issues regarding the sad condition under which we commemorate the sixth anniversary of the Arab uprisings. The first issue concerns a view that has spread quite understandably in the Arab region, according to which the lesson of the past six years is that the old order, despite its huge problems, was better than the revolt against it since the latter only managed to create a bigger disaster. The truth is that if we were to apply the same logic to any of the great revolutions in history, assessing them only a few years after their beginning, we would condemn them all... What started in the Arab region in 2011 actually is a long-term revolutionary process which, from the beginning it was possible to predict, would take many years, or even several decades, and would not reach a new period of sustained stability short of the emergence of progressive leaderships capable of bringing the Arab countries out of the insuperable crisis into which they have fallen after decades of rotting under despotism and corruption. This brings us to the second issue that it is necessary to emphasize on this anniversary of the uprisings. To say that the old Arab regime is better than the revolt against it is like saying that the accumulation of pus in a boil is better than incising the boil and letting the pus out. The tragedies that we are witnessing now are not the product of the uprising, but indeed the product of decades of accumulation of rot in the heart of the old regime. The 'Arab Spring' provoked the explosion of this accumulation, which inevitably would have happened sooner or later. The truth is that the longer the explosion was delayed, the more rot accumulated. If there is indeed one thing to be regretted in the Arab explosion, it is not that it happened but that it took so long to happen—so long that the old Arab order managed to achieve, to a great extent, its dislocation of Arab societies by means of tribalism, sectarianism, and various forms of cronyism, not to mention tyranny, state terror, and the lesser counter-terror provoked by governmental violence. ...The lesson that must be drawn from the recent historical experience by all those who suffer or have suffered from the Arab order that has been in place for decades—and this is the vast majority of the inhabitants of Arab countries—is rather the urgent need for an emancipatory progressive alternative to the rotten past that started to crumble six years ago, and will not cease collapsing whatever attempts to stitch it are made by its rulers. The year 2016 bears witness to this truth: it was not restricted to the tragedy of Aleppo, but started with a local uprising in Tunisia and ended with massive social mobilizations in Morocco and Sudan. The danger that threatens the Arab uprising is not the continuation of the revolution—its termination would indeed be much more dangerous than its perseverance—but the persistence of its lack of organized progressive forces capable to rise to the huge historical challenge that it faces. We are like a people that started coming out from the land of slavery and now face the threat of getting lost in the desert to be aggressed by ferocious beasts while searching for the promised land. To guide us towards this goal, we need a “modern Moses”: not a heroic individual leader but rather a collective emancipatory and democratically pluralistic project that champions the image of the new society to which we aspire." I think something important is missing in this powerful narrative. Achcar would have us see Arab Spring as a minute in the hour of revolution-making, an hour that has its reversals but moves relentlessly across the clock of history. But is it so clear that we are watching the same clock? Or, rather, is it the case that such major defeats create a vacuum on the side of “progressive forces” that requires starting anew—from the beginning of time, as it were. If that is the case, or, perhaps better, to the extent that is the case, we should have a more careful view of when to spark uprisings, a better understanding of the rootedness of our forces in the depths of the lives of everyday people, and a more conscious view of the requirements for organizing a successful revolution, before we call upon “the people” to topple existing regimes. My concern is especially focused on what happens in the United States in the wake of both the Trump and Sanders campaigns. Too much depression about the former is one danger; too much euphoria about the second is the other. We are in a period, both in the US and the world as a whole, when we need to carefully build opposition at the base of society, develop relationships between oppositional groups so that relationships of solidarity can be forged and action be taken that is aimed at the middle-levels of power, and only as a third act to a nonviolent (at least in the US) revolutionary drama attack the centers of oligarchic power that now rule the world. I share Achcar’s hope for “a collective emancipatory and democratically pluralistic project that champions the image of the new society to which we aspire.” I caution against thinking demonstrations in Tahrir Square, the Capitol Mall, Tiananmen Square, Puerta del Sol Square or its counterparts throughout the world are sufficient to reach that goal. No, the organizing task is a more complicated one than that. Everyday people and their everyday institutions (unions, centers of worship, clubs, interest groups, sports teams and more) need to own the effort so completely that society cannot move forward without their aspirations being taken into account. (A longer review of the great political photographer Danny Lyon's photo show at San Francisco's De Young Museum is available on the Stansbury Forum.) I met Danny Lyon in 1963 in Ruleville, Mississippi. I was on the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) visiting the Delta town in Sunflower County (home of Sen. James O. Eastland, one of the most notorious racists of the period) with Bob Moses, SNCC’s Mississippi Project Director and Martha Prescod, a young African-American University of Michigan student volunteer who was there for the summer. Danny took a picture of us talking with a local woman sitting on her porch. The picture became well-known because it was used on the cover of a widely distributed SNCC flyer. The story it told was that we were trying to convince the woman to register to vote. But Martha recently reminded me that we were asking directions!

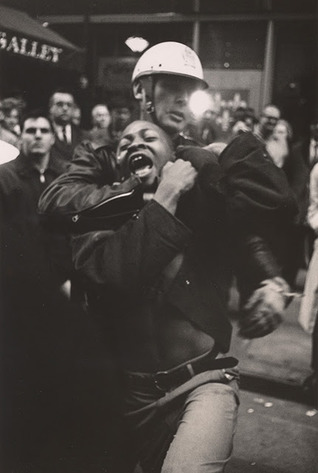

“You put a camera in my hand, I want to get close to people. Not just physically close, but emotionally close, all of it.” – Danny Lyon “Clifford Vaughs, another SNCC photographer, is arrested by the National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland,” 1964. Collection of the Corcoran/National Gallery of Art, CGA1994.3.3 © Danny Lyon, courtesy Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York Of his civil rights movement photos, Julian Bond said, “They put faces on the movement, put courage in the fearful, shone light on darkness, and helped to make the movement move.” Lyons was one of a number of photographers assembled by SNCC Executive Director Jim Forman to be chroniclers of The Movement (we always capitalized the letters “T” and “M”); he and Matt Heron are the best known of them.

Trump Racists? Were whites who voted for Trump racists? If a white voted for Obama in 2008 or 2012, but voted for Trump in the 2016 election, was s/he not a racist? I think there is no adequate answer to these framings of the question. We cannot understand what is going on in the country if we limit ourselves to questions of this type. Instead I propose questions that ask the details about what happened in circumstances when white-black (or any other people vs. another group of people) unity overcame otherwise divisive understanding of self- interest and prejudicial views of “The Other.” To do that requires telling stories, not truncated questionnaires that ask for yes/no or ranked short-answers, nor even the answers from the hot-house context of a focus group—no matter how good the facilitator is. Labels are static: they describe someone at a point in time. People live in dynamic, always changing, circumstances. The question is whether people with small “d” democratic values can successfully engage others who may disagree with them. The interplay of class and “identity” (as the term now is widely used to describe statuses other than class) needs more discussion if we are to win the support of white working class people who voted for Donald Trump. To win issues of the latter category, one set of alliances is made. For example: immigration reform advocates make alliances with corporations that want to hire cheap labor; and the National Women’s Political Caucus recruits, trains and supports pro-choice women candidates for elected and appointed offices at all levels of government regardless of party affiliation. I have black acquaintances who support Clarence Thomas because he’s African-American, despite the fact that he voted to end Deep South protection of African-American voters in the Shelby v Holder case. And I have women friends who agreed far more with Bernie Sanders than they did with Hillary Clinton but supported her to “break the glass ceiling.” To win issues of the former category, minorities make alliances with “whites,” typically to form unions but also in anti-freeway, urban renewal, massive development, affordable housing and other issues. When the community campaigns are used to form or deepen on-going relationships (as in multi-issue community organizations), the possibility exists to transform old prejudices—as the stories above demonstrate. So, too, can relationships in a multi-ethnic/racial union change attitudes and understandings of “white” members. The dominance today of “identity politics” precludes these latter possibilities—opening the door for the demagoguery of Donald Trump. But minorities and women have separate battles that need to be fought as well. Achieving a strategic balance is necessary. It is also difficult to achieve. Organizing Peabody Coal An old-timer I met in the early 1960s, who worked as an organizer for the United Mine Workers Union in the 1930's, told me this story about how he organized prejudiced white workers at the Peabody Coal Co. in Kentucky (but it could have been elsewhere in the South): Organizer : "Wanna talk about the Mine Workers Union?” White Worker: "Ain't you the Union let's in the niggers?" (When he heard that the organizer would take the white worker by the arm and walk with him until they saw a black worker.) Organizer: "See that fella over there?" (Organizer points to the black worker.) White Worker: "Yeah." Organizer: "Who's he work for?" White Worker: "Peabody." Organizer: "Who do you work for?" White Worker: "Peabody." Organizer: "You think about it; we'll talk more later.” Eddie Wafford Shows Up (You’ll Quickly See My Debt To The Peabody Coal United Mine Workers Union Organizer) I grew up in the Sunnydale Housing Project, at the western edge of Visitacion Valley, a neighborhood in San Francisco. Twenty years after I left, I returned as the lead organizer for what was initially the Visitacion Valley Organizing Committee (VVOC), an effort to build a multi-issue federation that would be a people power organization for the mostly- low-to-middle income residents of what was then a very racially and ethnically diverse neighborhood. Eddie Wafford was a retired Teamster Business Agent living in Visitacion Valley. He shared the anti-Black prejudices of many of his fellow Irishmen in the neighborhood. But he was a member of the Visitacion Valley Improvement Association (VVIA), a member organization of All People’s Coalition (APC), a multi-ethnic and racial federation that had supported VVIA on a couple of issues important to them and their members. VVIA joined APC because it need the power of others in the neighborhood to win a couple of issues important to it. About a year after those victories, with APC organizing staff assistance, the tenants in the 500+ units high-rise, 80% or more African-American, Geneva Towers formed a tenant association to negotiate with their landlord about a number of matters, including a major rent increase. Efforts to negotiate broke down. Direct action became the order of the day. Eddie Wafford showed up on a Saturday morning to ride a rented bus to the Towers owner’s home in nearby fancy Marin County. Eddie was one of a number of whites from the neighborhood who participated in the day’s action. By that time I’d gotten to know him pretty well. Given what I knew about his feelings toward blacks, I was a bit surprised to see him, and said so when I first saw him that morning. On the way home from the picketing, he and I had this conversation: Mike: "I was a little surprised to see you here today, Eddie." Eddie: "Why’s that, Mike?" Mike: "Well, you know, you told me a while back you didn’t have much use for Black people, particularly those living in the Towers." Eddie: "Aw, that was before I got to know them and they showed up for me and Little Hollywood. This is the least I could do." Mike: "So how do you feel about the Towers people now?" Eddie: "There’s some real nice people there, Mike." Mike: "Whose interests do you think were served by the way you used to think about the Black people there?" Eddie: "What do you mean?" Mike: "You think about it; we’ll talk more later." Eddie and some of his VVIA friends concluded their interests were better met in relationship with people they hadn’t wanted to work or associate with in the past. I wouldn't have gotten to talk with the VVIA people if I had “led with race”--telling them they were wrong about their racism, were “privileged whites” or whatever. A Different Approach To Racism (and Other “Isms”) My conclusions from the above experiences:

Contrary to what most sociologists and "leading with race" organizers say, peoples' prejudices can quickly be put on “the back burner” and soon fade to the background when the circumstances are right and the conversation based on those circumstances provides a new way to frame reality. Elections Sum Up What Has Preceded Them: You Pay the Price for What You Didn’t Do Earlier and That Bodes Ill for the Future

Organizing across racial lines, and other lines that divide a potential majority constituency, is a year-round proposition that will bear fruit at election time. Also note that for these stories are in specific local places. That’s where organizing has to begin because it’s where continuing relationships can be established. Finally, it’s where victories can be won as a result of struggle and solidarity. Without these victories, the fragile unity that begins such efforts will fade into the past, and old prejudices will return. In the absence of this kind of organizing, the kind of campaign that Donald Trump won is likely to gain traction in the white constituencies he appealed to. And consider this: if there are not organizations of the kind described in this discussion, what would happen if in a next election a Sanders—whether him or someone like him—wins? It is impossible to conceive a US government that could quickly reverse what has been going on for the past 50 years. In the absence of a rich civil society infrastructure that can be part of a process of social transformation, the promised transformation of a “progressive” electoral victory will die on the vine, its participants at the base feeling betrayed by the candidate(s) they elected. I’ve focused here on organizing not because electoral mobilization is unimportant but to argue that transformational mobilization cannot take place without the kind of organizing that is described in these stories. This kind of organizing can overcome the “isms”, not simply for a single election cycle when the isms are momentarily overcome by consumers who buy the same product (as they did with Barack Obama) but for the long-haul struggle that will be required if we are to come close to what Bernie Sanders advocated, let alone a more participatory, egalitarian and democratic society that we might imagine. When you ponder Trump’s victory, consider this e-mail from a union member to one of his union’s leaders:

You and me have went back and forth on this election. I want you to know this: I didn't vote for my retirement. I didn't vote for my Healthcare. I didn't vote for my union membership. I voted for my son. Because I just didn't see a future for him if we elected Hillary. I actually voted for Obama in the last two elections. Now, I stand here and tell you that if we lose our retirement, I will not bitch. If I lose my Healthcare, I will not bitch. If my tax rate goes through the roof, I will not bitch. I cast my vote and I will stand behind it. No matter what. What I say to you and every elected Union Leader is this: “The majority of your membership just voted against what you all thought was in our best interests. Our Union Leadership has lost it’s base. But now we need you more than ever. Fight like your the third monkey up the ramp to Noah's Ark and its just starting to rain. Protect what's important to us. Do you want the membership back? Then do what you say you will. Fight for us. The essential point is that Trump was a vessel in which people could place their anger at what has happened to them over the past ten, twenty…fifty years. [B]oth Brexit and Trumpism are the very, very wrong answers to legitimate questions that urban elites have refused to ask for 30 years…since the 1980s the elites in rich countries have overplayed their hand, taking all the gains for themselves and just covering their ears when anyone else talks, and now they are watching in horror as voters revolt. Vincent Bevins, Los Angeles Times. Some Details On Why He Won On a more technical level, these are factors that I think led to his victory:

Racism I think it’s an oversimplification to view the Trump election as an expression of racism in the country. No doubt among his constituents there are racists, and no doubt some of the things he said were racist. There’s nothing on the face of it that makes the Trump voter whose letter I’ve reproduced above a racist. On the Terry Gross show, on the day after the election, she interviewed Atlantic writer James Fallows. He’s spent the last three years visiting small town, middle America. His account was different. In some places, there are significant numbers of relocated immigrants from the Middle East—he cited Erie County, PA as one of them. In his conversations with them, they described a welcoming atmosphere there. Erie voted Trump. In another small town, a near-majority of Latinos exists where there was a shrinking older Anglo population in what was a dying town. The old-timers attribute the town’s re-birth to the new immigrants; they like the new Mexican restaurants and taco trucks. They vote for school bonds even though none of their kids are now in public schools. Fallows had more to say along these lines. Having spent several years in and out of rural Nebraska at the height of the farm crisis, his stories of these towns rings true to me. Trump demagoguery will give legitimacy to public expression of views that were held privately, or only shared among friends. At the same time, he spoke in some black churches in the last week-or-so of the campaign—hardly something any true-blue racist would have done. He made a point of asking for Ben Carson when he addressed his supporters on election night. It’s far too simple to conclude he is going to pursue a racist agenda as president. He might, but let’s see. As one journalist put it, "Low-income rural white voters in PA voted for Obama in 2008 and then Trump in 2016, and your explanation is white supremacy? Interesting.” Which isn’t to say that racism isn’t a major issue in the country. Strategically, minority community and immigrant rights organizations should ask themselves how they can develop relationships with this constituency. A serious discussion of that question is a pre-condition to building left-populist coalitions that can win legislative and electoral victories that address economic and racial injustice. Positives In The Negative? Organizers always look for the positive in the negative, and vice versa. I think there may be some:

Note that I distinguish between mobilizing and organizing. That’s deliberate. The two are too often conflated—a serious mistake. We need a mobilizing organization that can build upon the Bernie Sanders campaign and the Hillary Clinton defeat. Mobilizing is what Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference did in the south. We also need vital union locals and community organizations that can express the values and interests of this group in a continuing way, and create a sense of community among them that is not based on fear of, and contempt for, The Other. Organizing is what the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee did in the south, and what Saul Alinsky did in the north. (Here are some excerpts from my DISSENT Online review of a recent biography about Bob Moses. Please take a look at the full review here. Your comments would be appreciated!)

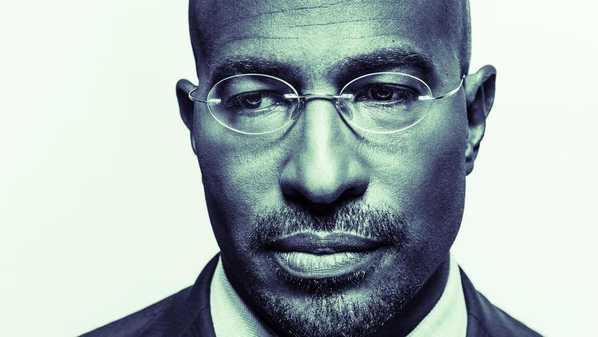

Robert Parris Moses was born in Harlem in 1935, the depth of the Great Depression. He was raised in a public housing project (which in those years was a step up from slum housing; I grew up in one), worked in a black-owned milk cooperative as a young boy, and had both Christian and pan-Africanist influences in his extended family upbringing. His grandfather was a respected progressive Baptist clergyman and former black college president; an uncle headed a branch of the NAACP; aunts were militant defenders of black rights; race and politics were continuous topics of conversation at home. His mother was a strong woman, a high school graduate who’d planned to go to college before marriage took her in a family direction. His father involved him in political conversations, always emphasizing the “little guy,” and taught him how to read people by listening and paying careful attention to them... From Ella Baker, Moses learned an elaborated view of grassroots organizing. Her aphorism, “strong people don’t need strong leaders,” would become a SNCC theme. Among the strong people Moses met on his trip was Amzie Moore. A veteran of the Second World War who had become an independent businessman in the Mississippi Delta, Moore was looking for a way to break voting barriers that resulted in almost no black voter participation in towns, counties, and the second congressional district of the state, where blacks were a majority of the population. Moore took Moses in and made him family... Many of us believed the MFDP’s challenge would be successful. With hindsight, it is easy to say we should have known better. Two rules of power operated against MFDP: first, when you borrow someone else’s power (in this case the national liberal-labor-civil rights organizations), if your and their interests diverge, theirs will prevail. Second, it is short-term, not long-term, interests that typically determine political decisions and outcomes. When Lyndon Johnson turned the screws on his liberal and labor allies, they capitulated and abandoned their initial support for the MFDP challenge... Typically, major defeats lead to disarray and conflict among the defeated as they seek to explain why their anticipated victory was not realized. I want to note three consequences of defeat here... Reading Visser-Maessen’s biography brought back a flood of memories of my time on the SNCC staff and my experiences then with Moses as well as the rest of the remarkable young people who made up that organization. But you don’t need to have had those experiences to appreciate the book. It will bring the tumult, vitality, hope that turned to despair, and intellectual debates of those times to anyone who reads it. The lessons in this book are as important to our country today as they were half a century ago.  (Van Jones, former White House staffer in the Obama Administration, now TV commentator on CNN, and long-time activist in the African-American community, produced a remarkable exchange between himself and a “white” Trump-supporting family in Gettysburg, PA. Watch the video exchange here. I think you’ll be moved by it, and learn from it. This is the first segment of what will be a three part series (it’s about 10 minutes long).) Here’s a little more about it:

Van Jones' new Facebook video series aims to humanize political adversaries through in-person interactions. Jones said he was trying to prevent what he calls the “#NextCivilWar” by engaging with a family supporting Donald Trump in their living room. “I feel like we’ve gotten this thing in America now, where we talk about each other, we never talk to each other,” Jones says, explaining the reason for having the conversation in the first place. “We’re here in Gettysburg, where there was a civil war because Americans couldn’t work it out,” Jones went on. “And I’m worried that we’re gonna have another civil war - or is this a civil war?” One family member agreed that the country stood on the brink of an armed conflict, claiming he knew people willing to take up arms if Hillary Clinton was elected, even if he wasn’t willing to do so himself. “A lot of it’s gonna rely on the way this election ends up,” the man said. “Hillary gets in, there could very well be a civil war.” From there, the conversation turned more substantive--if tense at times--covering issues like regulation, trade deals and immigration. Kimberly Fean Corradetti, the host who welcomed Jones into the house, lamented that Americans without a college degree could no longer get decent-paying manufacturing jobs. “These jobs have left us within the last 25 to 30 years--they’re gone--because so much federal regulation has strangled business - strangled ‘em,” she said. Then Jones confronted his hosts with the elephant in the room--race--and specifically Trump’s race-baiting rhetoric, including his comments calling Mexicans “rapists.” “So he’s a horrible speaker,” Corradetti said, adding that Latino immigrants offended by Trump’s comments calling Mexicans “rapists” should “toughen up.” “No, you don’t have the right to tell someone else how to deal with the pain that they’re going through,” Jones responded. “If you say, ‘You should have a thicker skin,’ if you say, ‘You have got to get over yourself,' I’m gonna hear that as, ‘This person does not respect me, does not understand me, does not know what I’ve gone through.’” Here’s what I think is missing in Van Jones exchange: on the video you will see Corradetti point to pictures on her mantle and tell him, “those people—no doubt her family—were all immigrants.” Given her last name, I think it’s safe to assume that at least some of them were Italians. If you’re as old as I am, you may remember when Italians in this country were “WOPs” (WithOutPapers). Sound familiar? Had I been at the video session, and were I Ms. Corradetti, I might have responded to Van Jones, “There was nobody in those days to tell people using that term that they shouldn’t. Nobody censured them on campus for ‘hate speech’. While her choice of “toughen up” might not have been the best of phrases, her point is one made by a lot of white-ethnics in this country: “We made it without government telling people what they couldn’t say; there wasn’t ‘political correctness’ in their day.” And they’d probably elaborate, “We made it without affirmative action, quotas or any other programs like that.” I hope the coming Van Jones discussions (there are two more) get into these issues, and clarify some of these questions. Until he, or any of us who care about the state of justice in the United States, does, we won’t get past the barrier that now makes adversaries of people who should be allies. (Friends, I think this article by Michael Lerner, "Psychopathology in the 2016 Election," (published a couple of days ago in Tikkun) is a very important piece. Please take the time to read it. My comments and disagreements are in a letter I sent to Micheal, posted below. Your thoughts would be appreciated!)

Michael, I generally am in agreement with your analysis, in "Psychopathology in the 2016 Election," of Trump's appeal. This is an excellent piece, and includes a lot of powerful images and argument. Your use of popular media to illustrate your points is terrific. Please consider making it into a pamphlet, perhaps with illustrative photos and graphs. Should you decide to do that, I offer my editing services (no charge) to strengthen it along the lines of what follows. Substantively, there are two areas that I think are weak, and could be strengthened without detracting from your major argument.

To be a winner in this society requires one to maximize one’s own self-interest, which is often achieved by perfecting the techniques of manipulating others. This is evidenced in ‘reality’ television shows such as The Apprentice, The Bachelor/The Bachelorette, and Survivor that represent a societal assault on generosity and a glorification of selfishness. and The legitimate attempts by liberal and progressive movements to provide well-being and equal rights for oppressed groups were instead described as quests for unfair economic and social advantage, won at the expense of white working-class people whose economic, psychological, and spiritual suffering were the products of these allegedly narrowly focused self-interested groups who didn’t care about the welfare of others. Here, I think you get it right: The triumph of selfishness as common sense creates a huge psycho-spiritual crisis and a society filled with deeply scared and lonely people. and Not only do the values of selfishness and materialism that permeate the capitalist marketplace infiltrate people’s personal lives, undermining family stability and causing great distress, but the capitalist society justifies the huge wealth inequalities by convincing people that where they have ended up in the economic struggle of all against all is a function of their own merit—how smart they are, how hard they’ve worked, to what extent they have the personality traits that will ensure their success, etc. I think these are proper uses of "selfishness," and powerful ones. I prefer this formulation:

This way of distinguishing selfishness from self-interestedness opens up great opportunities for your case. You now cut yourself off from them. Here's a story that illustrates my point. When I'm organizing in a low-income, crime-infested, neighborhood, I hear a lot about fear of crime. In response to it, those who can afford to buy external metal doors, bars for their windows, alarm services if they can afford them (which most can't). The problem, of course, is that this approach leaves the streets to the criminals resulting in purse snatchings, car break-ins and muggings. People know that. When I propose they organize themselves to watch over their streets, know their neighbors so that when someone strange goes into a house they know s/he probably doesn't belong in (so call "911"), organize a "block watch" with the local police department, demand increased police protection, etc. I begin with their self-interest--their desire to protect themselves and their neighbors from crime. When they get involved, I can soon get them to support programs for youth--to improve their job opportunities, provide after school recreation programs, etc, etc. But my beginning point is self-interest. By denying self-interest and conflating it with selfishness, you rob yourself of these kinds of opportunities that are found in community organizing. For that matter, the best of the CIO unions used self-interest as a tool to organize workers into union based on principles of solidarity: "an injury to one is an injury to all", "black-and-white/unite-and-fight", etc. You write, But since government itself provides ‘objective caring’ in the form of material benefits, but rarely provides ‘subjective caring’ in the form of treating the recipients of government services with a deep sense of respect and appreciation, it’s all the easier for the Right to foster this resentment at government. I think a term other than "objective caring" would be better. Perhaps "objective benefits". You make yourself vulnerable to "nanny government" critics when you don't need to. This point that you make: Particularly in the post-Civil Rights Movement period of the late ’60s and from then on, the Right has addressed American’s underlying psychological pain of alienation and sense that everyone is out for him or herself, and spiritual longing for meaningful lives, by blaming the most vulnerable in our society, those who were seeking to rectify long histories of oppression—African Americans and other peoples of color, then feminists, gays and lesbians, young people, and more recently undocumented workers and refugees. The Right claimed that these groups were responsible for introducing the selfishness and materialism that was corroding societal values and destroying families. seems like a stretch to me. The economism you describe here, Deeply enmeshed in their own religiophobia, people on the Left rarely open themselves to the possibility that there could be a spiritual crisis in American society. seems overstated to me. I know a lot of liberals, progressives and leftists who now would agree there is a spiritual crisis in the country. Beware of being dismissive of people who otherwise are your natural allies. Again, in this, This gets intensified when the Left fails to expose these dynamics to working-class people, instead dismissing white working-class men as inherently racist, sexist, etc. you make a blanket indictment of "the Left" which is neither helpful to your cause nor, from my experience, accurate. This, Many people are sick and tired of the empty promises of centrist politicians on the Left and Right. is a rather peculiar formulation. If they're centrists, how can they also be on the left or right? Your later use of "moderate middle" is far better. There are other places where I think you similarly use to broad a brush in criticizing "the Left;" indeed your anger with the Left runs through the piece in ways which, in general, don't serve your case at all. Which isn't to say that a more nuanced version of the point isn't accurate! As you would expect, I don't agree with this: We will need a domestic Empathy Tribe—people who have learned the skills of empathic communication and who are willing to go door-to-door in the old-fashioned style of community organizing, but with a very different message than community organizers conveyed in the past. I think it also reveals an ignorance of what community organizers "in the past" did or conveyed. (See People Power: The Community Organizing Tradition of Saul Alinsky for a lot more on the point. I co-edited it with Aaron Schutz.) The fact that you note the absence of your perspective over the past three decades might suggest that there are some errors in how Tikkun and the Network of Spiritual Progressives are presenting their case. You, instead, seem only to focus on what's wrong with Sanders, et al. Do I sense powerlessness here? I suspect this problem is in your preliminary vision statement, though I have not yet read it. I think you will find the piece, "How Half Of America Lost Its F**king Mind", by David Wong, from Cracked, 10/11/16, of great interest. He claims 4,808,922 views. I think we might learn something from him! Warm Regards, Mike

|

AuthorMike Miller has had almost 60 years experience as a community organizer. Before founding the ORGANIZE! Training Center in San Francisco in 1972, he was a founding member of SLATE and an SNCC field secretary. In 1967, he directed one of Saul Alinksy's community organizing projects. Archives

February 2018

Categories(The quote at the top of the

page is by Desmond Tutu.) |

(415) 648.6894 [email protected] 442 Vicksburg, San Francisco, CA 94114

Copyright© Since 2016, ORGANIZE! Training Center. All rights reserved.

Copyright© Since 2016, ORGANIZE! Training Center. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed