|

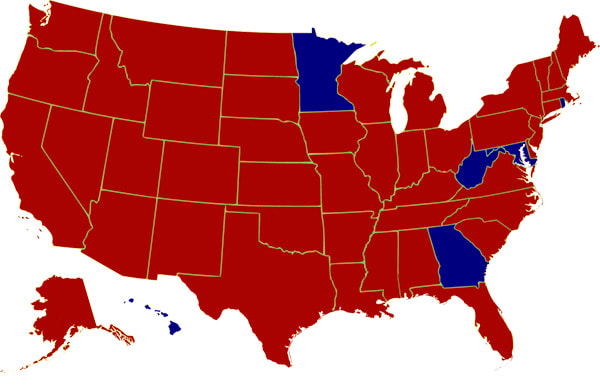

As did the Ronald Reagan presidential election victory in 1980, so the Donald Trump victory in 2016 is forcing many organizers to examine or re-examine their views on electoral politics. I would like to propose a context for this thinking.

Consider these propositions:

This is the larger “build” that should be guiding us. If we are successful, politicians will increasingly have to reflect where our side stands in how they vote and campaign. We are a long way from that today, but that’s where we need to be heading. I don’t think we sufficiently applied these ideas in the post-Reagan era. As a result, we ended up with a sometimes slow, sometimes fast, but at whichever speed continuing drift toward concentration of wealth and power in the hands of an ever-fewer number of people, disastrous foreign policy decisions and unchecked empire, ecological disaster, and “neo-liberal” economics. We need to do better next time around.

1 Comment

Preface

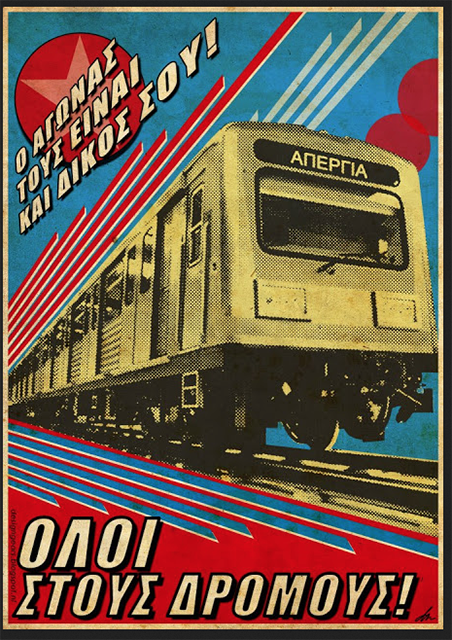

What I know about Greece and Greek politics can be put in a thimble, and probably a small one at that. So these observations and questions need that preface. As further preface, it is very difficult to apply lessons learned in the United States to anyplace else without contextualizing them in the new setting. That requires intimate knowledge of what is happening on the ground—so what follows are friendly speculations. All the political Greek people we’ve met have been warm and hospitable in their welcome to us, Americans whose political and economic structures (government, financial and corporate), along with the European Union, European Bank and International Monetary Fund are largely responsible for the mess in which their country now finds itself. To be sure, there is complicity in past behavior and decisions made in Greece. But it’s not these macro questions that I want to consider here. Local People We (my partner Kathy Lipscomb* and I) have now met with a public school teacher, taxi driver, waiter (who is also a university graduate in political science), tour guide, night shift security guard and a well known Greek actress ALL of whom blame Syriza (“Who we are” – Syriza) for the current mess, are fed up with politics and politicians (“they are all alike”), and think Syriza (has done nothing for the Greek people or, even worse, point to things Syriza (Here) did (ignore the referendum results), or is doing (see below), that are making things worse. We have also met with an internationally known political scientist who is active in Syriza, and who is interviewed regularly in various English language left journals, and a Syriza political appointee who is the national coordinator of municipal mayors. The two of them have elaborate explanations for everything Syriza has done or not done. The bad things, in their views, are for the most part the result of constraints imposed upon them by The Troika. They note good things that are done quietly, with no fanfare, under the radar. However, these seem to be so under the radar that none of the other people with whom we spoke mentioned them; indeed they said things that contradicted the claims. Our pro-Syriza informants also indicate that mistakes were made, but they believe these had more to do with Syriza strategy than with decisions that hurt the Greek people. The clearest example of a bad thing is the story we were told about home foreclosures. There is a high percent of homeownership in Greece. Until recently, we were told, there was an ‘umbrella” that protected a home owner in his/her residence, though it didn’t protect additional property from foreclosure. Syriza, we were told, is responsible for removing the umbrella. Not only that, when the protection was first removed demonstrators appeared at the foreclosure proceedings making it impossible for judgment to be rendered. In response, Syriza made the procedure an electronic one. You now receive an e-mail informing you of the foreclosure as a “done deal”. Another example we were given, Syriza is further eroding the pensions for which people paid during their work lives. That is a disaster for Greek retirees: there is only a public retirement system. Workers paid 18% of their wage into this system; employers paid 28%. The government has now more than once cut retiree payments. What is the truth? We are in absolutely no position to tell. I can say with some confidence that not one of these informants was disingenuous; they firmly believe what they told us; none had a pre-disposition against Syriza and, in fact, most of them had been Syriza supporters, and voted for Syriza in the last election. Now, they told us, they either will not, or do not know if they will, vote. And, if they decide to vote, they have no idea for whom that will be. Is there a way to understand these apparently opposing views of the same facts? There is clearly a participation and perception gap between people we met who were Syriza supporters and those now actively engaged in Syriza. In what follows, I use a framework that I apply in my understanding of what’s going on in the United States. Does the application work? Is it appropriate? I’ll leave that for the reader to decide. What’s Up? In a democratic and participatory union, workers may decide to strike because the offer being placed on the table by their employer is inadequate. They might conduct an effective strike, and still be stonewalled as far as any improvement in the employer’s offer. At some point, the workers might decide they’ve put up as good a fight as can be waged, and their own economic circumstances are such, or the increasing presence of scabs is such, that they have to end the strike, return to work, build their strike fund again (if they have one), and wait until the next round of contract negotiations to return to the negotiating table from a position of strength. These workers are not likely to blame their leadership for the failure of the strike. The 1948 Packinghouse Workers Union strike is probably a good example of what I’m talking about. As every American trade unionist who cares about the future of the labor movement knows, what I just described is, for the most part, a memory of the past. It has been replaced by what people call “insurance policy unions”. You buy your insurance policy (pay your dues) and expect your benefits (advocacy—contract negotiations, and services—grievance representation). Thus the common phrase, “What’s the union going to do about ‘x’?” as if the union is a third party—separate from the member asking the question. What’s all that got to do with Greece, Syriza, and electoral politics in general? It seems to me in the nature of politicians and political parties in formally democratic systems that the party adopts a program, selects its candidates, and then determines a strategy by which to convince citizens to vote for it and them. But “convince” in the modern era is a tricky word because what it really means is to sell buyers (voters) a product (candidates and their program—which might have little to do with what they actually do if elected). At best, during an election a door-to-door mobilization takes place in which the candidate’s volunteers ask voters to support their candidate. Reasoning is not what takes place at the door because the canvassers are instructed not to waste time with opposition and, at best, to spend limited time with the undecided. Campaign imperatives demand this kind of behavior: there is an election that will take place on an already specified date and a majority of voters is required if the candidate is going to win. This imperative makes mobilization necessary and organization unlikely once campaign season has begun. It is not by accident that this kind of campaigning takes place. The gap between the political parties and their candidates, on the one hand, and the voters, on the other, is huge. More likely than canvassing, it is direct mail, social media and television advertising that are used to reach the voters (the market). In national campaigns this approach is built into campaign structures: campaign consultants, who are the principal operators of campaigns, are paid by a percentage commission on the cost of the medium used for reaching to voters. Door-to-door work gets almost no money because most of the workers are volunteers! Even in a campaign that is heavily dependent upon volunteer effort, the contact with the citizen is a fleeting one, and the follow-up is typically electronic, not personal except for election-day when the favorable voter is contacted to insure his or her turnout. Potential voters do not say about the candidates they support, “What are we going to do about ‘x’ (unemployment, student debt, immigration, etc)?” They want to know what the candidate is going to do about ‘x’. The very nature of the campaign process tends toward the separation of “the campaign”—candidates and their inner-circle, donors, leaders of key interest groups (whose members already think of their organizations as third parties), and activists. The question then becomes, “How deeply rooted are these activists in the day-to-day lives of the various constituencies addressed by the candidate?” My friend Herb Mills was chairman of a “stewards’ council” in the International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU). There developed under his leadership a widespread system of elected stewards at worksites. The stewards worked alongside other workers. There was little-to-no gap between them. They were the point of connection between a worker or a “gang” (a working group that unloaded cargo) and “the union”. There was no gap, no “what’s the union going to do about ‘x’?” question. In my experience as an organizer, “the activists” typically lack the rootedness in constituencies in whose behalf they believe their candidate will, if elected, act. Frequently they are sociologically very different: young, instead of spread across the age spectrum; “Anglo”, rather then reflecting the racial/ethnic diversity of the constituency; college educated, etc. They are people with whom I might agree on a very high percentage of things they believe. But they aren’t people upon whom I would rely to engage in a continuing conversation with the voters after the election, especially if the person elected had to make a compromise that appeared to violate the platform on which s/he had run as a candidate. Thus the activist isn’t likely to be able, over the long haul, to “deliver” at the base. Greece Application Is any of this applicable in Greece? People who know that situation far better than I will have to draw those conclusions. I hope the questions and observations are useful. I suspect that Syriza and its activists lack the kind of rootedness that is required for everyday voters to say about their plight, “What are we going to do to solve the mess we are now in?” Both our Syriza informants told us nuanced examples of how the organization is now supporting things like soup kitchens, community gardens, homeless shelters and other programs and activities to solve the problems of poverty. They also claimed that Syriza had expanded funding for education, and stopped some bad things from happening to pensions. They see Syriza as having an organic connection with the “social movements”. Yet the school teacher and her security guard husband made no connection between their volunteer time spent in a soup kitchen and Syriza. Similarly, other activities we heard about from our other Syriza-critics (retiree organizations and mobilizations, campaigns to save peoples’ homes, worker strikes, etc) do not seem to be viewed as an aspect of a larger movement of which Syriza is a part. Quite the contrary, Syriza is seen as part of the problem, not the solution. In the U.S. I think there needs to be a vehicle for “we”, and it is not a political party because the dynamics of parties don’t lend themselves to the effective creation of “us”. Is that idea relevant in Greece? One of our informants said that when her son arrived at the university to begin his studies there, nine different political parties had registration desks where he could join one of them. But there was no registration desk for a student union that enlisted the vast majority of students around a lowest significant common denominator program that represented their values and interests—for example their indebtedness and the almost 50% unemployment rate their age group faces. Similarly, there is no organization in the community that includes mothers’ clubs, soccer teams, retiree organizations, unions, interest groups of various types and others, and new groups that could be formed among the marginalized. Various interest groups engage in protest demonstrations, but only political parties seek to bring them together. Thus there is nothing outside the electoral politics process capable of defending and advancing a program, and effectively demanding of politicians that they implement it. Is something like that possible and/or desirable in Greece? I’ll wait to hear from them on that question. (*Disclaimer: My partner Kathy doesn’t agree with all that’s said above. These are my views alone. Readers of Stansbury Forum might want to look at my earlier post, “Syriza Prompted Musings”. To dive further into my thinking about Greece, see the attached article, “Reflections on Greece”.) Talking about Detroit, the movie, Kathryn Bigelow’s devastating and deeply moving film on the city’s violent summer of 1967, begins with the difficulty in naming the story it tells about the city. In an interview about the film, Bigelow calls it an “uprising”. Among many of my friends and acquaintances it is politically incorrect to call it a “riot”; their preferred terms are “revolt”, “rebellion” “insurrection” or “uprising”. Neither “riot” nor the latter four options work for me, so I've invented a few alternatives: “riovolt”, “reviolution” or “uprioting” —take your pick. If Detroit was an uprising/ revolt/insurrection/rebellion, then we need different terms for what Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Jemmy, Gabriel and hundreds of other slave leaders did. At a minimum, there is a dimension of planning and targeting in the latter that is absent in the former.

Detroit begins at a party, at an unlicensed after-hours club, celebrating the return of two African-American Vietnam war veterans. In the wee small hours of the morning, the cops raid the place and begin arresting the party-goers. Probably most of the people had more than a few drinks by that time. In any case, initially they were in good humor, trying to tell the cops they weren’t doing anything wrong. Things get out of hand. The cops rough-up some of the arrestees. A crowd gathers around the paddy wagons. A bottle is thrown at the cops. Glass is broken. The cops leave, looking for reinforcement, but the crowd remains. Pent up hostility toward the 95% white and widely known-to-be racist police force is expressed. Windows are broken, looting begins, alarms go off, fires break out, sirens are heard in the distance. From there things quickly escalate. To reveal them will take nothing from the drama of the movie, so, briefly, here are some: Congressman John Conyers appears and addresses a crowd, acknowledging the legitimacy of their anger but urging them to cease their activities. Windows continue to be broken. In one case, a man runs from a store with stolen property; he is shot in the back. He manages to get away, and crawl under a car. There, blood running from his body, he dies. At police headquarters, a supervising cop calls what happened “murder”. That is the only time we see a specific cop on the side of law enforcement. (While the National Guard, State troopers, U.S. Army paratroopers and Detroit Police are backgrounded as bringing the uprioting under control, the main character cops are engaged in lawlessness.) Another harrowing scene: a young black girl opens the window curtains in her living room. Scared cops see a gun rather than rustling curtains, and open fire. She is killed. There is an interlude: The Dramatics, an up-and-coming male gospel turned R & B quartet, is about to perform in a Detroit auditorium when the cops arrive and shut the concert down. The four young men make their way to The Algiers Motel where they join with other young blacks and two young white women. The why of the women’s presence isn’t totally clear: the cops later call them prostitutes (they weren’t); they describe themselves as visiting from western Michigan. One of them says her father is a judge. But how they ended up at a mostly-black motel should be made clearer. One of them helped in the making of the film, and says they were following “a band, an R & B group” they met in Columbus. An African-American security officer, Melvin Dismukes, is an enigmatic figure in the film. What makes him tick is never made clear. It should have been. On the one hand, he at times appears to go along with the cops at their worst. At other times he’s a careful calculator of the possible in an impossible situation and does what he can to diminish the evil, including saving the life of one young black man. He is so disgusted by the not-guilty verdict in the criminal case against the cops that followed the events at the motel that he vomits. But, according to the post-incident Citizens’ Action Committee, formed by a group of Detroit black leaders, Dismukes played a role in the murders. In an interview 25 years later, he said, “I had nothing to do with what they [the cops] had done. And to this day I still say the only reason my name was linked with them was to get them off. It would put less pressure on them if they could tie a black person in with it. Now you can’t make it a racial issue.” “The Algiers Motel Incident,” as the events there came to be known, is a horror story of police intimidation, brutality and murder. I won’t go into the details here. Suffice to say that the Dramatics make their way there from their cancelled concert. Initially, the motel is somewhat removed from the unfolding riovolution. That soon changes. A toy or starter gun (no bullets) is used by one of the men there in a pretended shooting of another man in the room. He falls to the floor in a pretend-to-be-wounded moment. When everyone realizes what’s taken place they laugh. Edgy cops across the street don’t. They assume they’re being shot at. The Algiers Motel Incident follows. It is a grueling, unrelenting, example of law enforcement at its worst. It also captures the power of the worst racist in the group of law enforcement people (state and local police, national guard and a security guard) who invade The Algiers to impose his will on those (except for one) who might otherwise have been unlikely to do what they did to totally innocent people. Three young black men end up murdered by cops. Bigelow puts human faces on the huge scale of the events that are here summed up statistically: 43 civilians killed, 33 of them African-American; more than 1,000 people injured; over 7,000 arrested; thousands of buildings destroyed, many never rebuilt; millions of dollars in damage. “It was as if God was saying, ‘I’m going to give you this test, Ike, and let you see how bad people can be, but I’m going to let you live through that,’ ” said McKinnon, who returned to work the next day. “I was never so afraid as those days in July during the riots.” The mid-to-late 1960s was a season of riovolts. The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 prompted dozens of them across the country. I was working in the Kansas City, MO African-American community when one erupted there—clearly provoked by local cops who tear-gassed non-violent marchers. They are scary! Predictably, none of the cops is convicted in the criminal trial that follows. A civil court case produces compensation for two of the families of murdered young men. As might be imagined, Detroit provoked strong reactions. Many were positive, and appeared in mainstream media. One white critic is incapable of seeing that an explosion like Detroit’s could happen today. Writing in The New Yorker, Richard Brody is offended that the film “suggest[s] that, in the intervening half-century since the events depicted in the film took place, little has changed.” Sad to say, there are still cities where police brutality is a continuing problem, and where similar riovolts might well take place. Bigelow sums it up: “These events seem to recur—this is a situation that was 50 years ago, yet it feels very much like it’s today.” Another, Angeleica Jade Bastien, is angered by what she saw and deserves to be quoted at some length: “Detroit” is ultimately a confused film that has an ugliness reflected in its visual craft and narrative. Bigelow is adept at making the sharp crack of an officer’s gun against a black man’s face feel impactful but doesn’t understand the meaning of the emotional scars left behind or how they echo through American history. “Detroit” is a hollow spectacle, displaying rank racism and countless deaths that has nothing to say about race, the justice system, police brutality, or the city that gives it its title.” Here are some facts about the “rioters” from a study done shortly after the events by the Detroit Urban League and the Detroit Free Press: “Rioters are different,” begins a survey-based article, “What Sets Him Apart?” Most striking, “Fifty-nine percent of the rioters were between 15 and 24 years old,” and, “60% were male.” They were twice as likely to have experienced long-term unemployment, though there “was no pattern to directly link rioting and low income.” The report finds deep alienation: “rioters profess to shun the American dream.” “Their attitudes “represent a bitter reservoir of resentment…” but there are contradictions: about three-quarters of the respondents “accept the traditional American belief that people with ability and drive get ahead and that people who are unsuccessful in the conventional sense should blame their own mistakes.” The grievances “that were associated most strongly with rioting were of a notably short term nature: Gripes against the local businessmen, mistreatment by police, lack of jobs, dirty neighborhoods, lack of recreation facilities.” The survey sums up its findings: “These, then, are the rioters: Young people, raised in the North, with little concern for their fellowmen and a frustration in meeting near-term goals—people susceptible to the black nationalist philosophy that the law and order of a white-built society is not worth preserving.” Editorially, the Free Press concluded, “…if the attitudes of alienated young Negroes are to change, the attitudes of the rest of society must change.” (The entire document is worth careful reading, and can be found here). These findings fill in blanks missing from the film. It does not provide context for what it so dramatically portrays. Perhaps it is too much to ask from a gripping moment-by-moment account of a brutal series of events. But the viewer who is not already convinced is unlikely to fully appreciate why these riovolutions take place. They are more likely to be viewed as riots, an insufficient concept to understand the events. An Eyewitness Story Ike McKinnon, a Detroit policeman at the time, reminisced about those 1967 events in a Detroit News account of an incident he experienced. He was in full uniform, completing a 16-hour shift, when he was stopped by a pair of white cops. This is what ensued: “I said ‘police officer. I’m a police officer,’ “They had their guns out. I remember one officer so vividly. He was probably in his late 40s. He had brush-cut, silver hair. He said ‘today, you gonna die (racial slur).’” It was as if things were unfolding in slow motion, McKinnon said, as he watched his fellow officer pull the trigger. He dove back into his car. “With my right hand, I pushed the accelerator, my left hand I steered my Mustang, and they were shooting at me as I drove off,” he said. McKinnon escaped uninjured, drove home and reported the shooting to a sergeant. It was never investigated. That was McKinnon’s first brush with death during those tense July days, but he said it wasn’t his last. “It was as if God was saying, ‘I’m going to give you this test, Ike, and let you see how bad people can be, but I’m going to let you live through that,’ ” said McKinnon, who returned to work the next day. “I was never so afraid as those days in July during the riots.” McKinnon would later become Detroit’s chief of police in the 1990s as well as more recently deputy mayor under Mayor Mike Duggan. Preface

I went to Miami, Florida on Tuesday, September 5 for several meetings related to a project I’m working on. While in the air, my hosts wrote an e-mail telling me not to come. Too late! By the time I arrived, things were shutting down in Miami. All my meetings were cancelled. My host advised me to move my return flight to an earlier date because it was unlikely that planes would be flying on Saturday, September 9. I did that. On Friday, September 8, at around 1:45 p.m., I left my airport area hotel and headed for Miami International Airport with a reservation for a return flight to San Francisco departing at 9:30 p.m. The experience at Miami International Airport was stressful. It was also instructive…on a lot of important things. The Story Lines I got to the Miami International Airport far in advance of my flight of my Thursday, September 7, 9:30 pm flight. I went to a line where I hoped I might move to an earlier flight. The people there had tickets, but also had luggage or some special circumstance—like changing your flight time. I was hoping to move to an earlier departure. The line moved very slowly. The up-side of the down was a chance to observe and talk with people. A young woman in front of me, and a 60ish woman behind me were my conversation companions. The young woman had her dog in a kennel, and a couple of over-sized suitcases. “I took everything I really care about. I think my apartment is going to be flooded,” she told us. She was pretty philosophical about it: “Things can be replaced; your life can’t.” The woman behind us was scheduled to leave for London on a 7:30 pm flight. When we moved only a few yards in a line that looked like it was a mile long, she got concerned and asked if we would let her move in front of us. No problem; by that time we were travel buddies. I watched her inch her way toward the front of the line, no doubt repeating her London departure time concern. She was quickly at the front. Lots of people said, “no problem,” and they weren’t her travel buddies. After barely moving for an hour-and-a-half, gave up. I punched my confirmation number into one of the computer terminals and I had a boarding pass…to go no place as things turned out. Like all the other lines in the airport, the security line was long. At least it moved more quickly than the initial line I’d been waiting in. Once through security, I head down the very long Miami Airport corridors to my gate. Dogs Lots of people were in the airport with their dogs. Most of them were quiet and friendly. The larger ones were already in kennels, but they were let out and held on a leash because everything was moving so slowly. If you’re traveling with a dog, and the dog is fairly small, it’s now relatively easy to take it on a plane with you. Pouch sits on your lap, and you hope the passenger next to you isn’t allergic. There were also some barkers, and some shitters too. You’d be amazed that owners of some of the shitters just left their piles. So who looks for dog shit when you’re walking down the hallways of an airport looking for your gate? Yeh, you got it, people stepped in it and dragged it around. And the custodial staff evidently had other priorities. On Board…and Not Once on my plane, we sat or rolled on the tarmac for almost three hours. Then, in order to avoid paying each of the passengers a big fine, the pilot returned to the gate and we were told to get off. (The fine is the result of a horrendous incident a number of years ago when passengers sat on a plane for hours, and the airline wouldn’t let them off. Now the Passenger Bill of Rights says airlines can’t do that. Too bad; there should be some flexibility. I think at some point we might have been able to fly, but rules prevented it. In addition to that problem, there were back-up problems with air control—they were on skeleton crew status because some of the controllers had earlier been sent home. There were also crew problems with maximum number of hours allowed in the air before a crew change is required. We also had a generous pilot who decided to wait for four passengers who were someplace in the airport but “on their way”. We might have been able to take off had we not waited for them. After returning to the gate, a small number of us left the plane. The remaining passengers staged a plane-in (a distant cousin of the 1960s sit-ins) and refused to get off. While they stayed, we wandered back and forth between the gate and the American Airlines Customer Service counter trying to find a way to depart. The counter personnel were overwhelmed. There were two of them! Nobody got anything from their wait in line because by that time all flights almost anyplace had reached their maximum 50 stand-by passengers. Whoops. Forgot. I could have gotten on a plane to Santiago, Chile if I’d had my passport. Oh well; another time. More Lines A little bit of everything comes out of people when they are frustrated in line. We had our cursers: “What the f..k are you all doing; I’m going to sue the shit out of American Airlines…” You get the picture. Then there are the thoughtful people: sharing a blanket with a little kid; offering to go to a restaurant and get food; generally trying to be helpful. We had a couple of comics too. Sorry, I can’t recall any of the jokes. Most people were just frustrated. That’s the group I was in. The check-in counter agents must have called the cops because of the rowdiness of a few passengers in the line. Several deputy sheriffs showed up…just in case. The American Airlines people on the ground were totally unprepared to deal with what was going on. Later in the day, someone bought snacks and brought pillows to the customer service counter area. Luckily for me, from who-knows-where, some wooden rocking chairs were brought out to the gates and the service counter area. They had high backs, so were much more comfortable than those low-back row-seats that you no longer can sleep on because there are arm rests between each seat. But the comfort didn’t last long; the hard wood and my butt parted company after an hour. It finally became clear around 3:00 in the morning that none of us would go anyplace. So I found an energy source, plugged in my computer power chord, and caught up on correspondence and project I’m working on. What’s Next? The last thing I remember before falling asleep is an announcement telling us “you can’t stay at the airport; buses are going to arrive around 3:00 or 4:00 p.m. today to take you to shelters.” My inclination was to hide out in a men’s room, wait for the busses to leave, then find a seat in the empty airport. I thought I’d rather be there than in a gymnasium with several hundred other people, their dogs, their farts and burps, germs, etc. Didn’t know if I could pull that off, but it was my plan. My main concern was not getting one of my chest colds that knock me out for 10 days. I can put up with everything else. I awoke from my six-and-a-half hours of sleep on Friday, September 8, at about 12:30 p.m. Still a bit groggy, I headed for what looked to be the most comfortable restaurant that was still open. That was the Irish Pub where my Irish omelet was perfect. Given my plan to remain in the airport for the duration of my stay in Miami, I thought this was a good place to start: comfortable seats, CNN TV, good food, good service. One of the waiters even scoured the restaurant to find an electric power outlet so I could plug in and restore my computer battery. He even looked behind the TV screens. No luck. Oh well. But around 2:00, it was clear they were shutting down. “Can I hang around here?” I asked. “No, sir, we’re closing” “I’ve got no place to go.” “What? You don’t have a place to stay, and you don’t have a fight?” “No, neither one.” “Let me ask.” That was a combination of my waiter and the manager, both of whom are Latinos who talked with one another in Spanish that was too rapid for me to do more than catch a word here-and-there. The manager checked with his boss, also in Spanish. “Sorry, sir, but you can’t stay. But let me see if I can make you some sandwiches.” That was encouraging. I figured my safari in the desert of Miami Airport might be well served with an occasional bite to eat. No deal. “The kitchen is closed.” Down the hallway from Gate D-37 where customer service is located there was still a Hudson News store open with various packaged goodies. I stocked up: two healthy packages, and my sweet tooth won out on the third. “What the heck”, said I to myself, “I’m going back to American Airlines (AA) customer service. Maybe something is breaking there.” Now, instead of last night’s crew of two counter staff, there were eight. And the line was shorter. When I got to the counter, lo and behold there was one last flight to Dallas, and there were seats on it and a decent connecting flight to San Francisco. Turns out AA made a decision to put passengers on the flight that was taking their remaining staff out of Miami Airport. So, believe it or not, I got a ticket on a plane with a number of pilots, flight attendants, ground crew, who knows who else from American, and a lucky umber of “civilian” passengers. Further believe it or not: there are at least a dozen empty seats on the plane. The decision must have been made at the last minute to let passengers aboard, and there weren’t that many of us left in the airport—at least at the customer service counter. Back On A Plane By 3:30 pm, I was on the plane. But I was now leery; I’d been on a plane earlier: “Don’t count your chickens before they’re hatched,” says I to myself. To make matters more suspenseful, there were a couple of false starts: first, the doors were shut—you know the message, “attendants lock your doors and prepare for departure” (or something like that). They did, and they were belted in their seats when they got up and opened the doors. More passengers. Breathe a sigh of relief: people getting on is good; people getting off is bad! More waiting. Pilot announcements that explain: “due to the skeleton air control crew, planes are spaced with 20 miles between them.” Then, “the plane to your left isn’t leaving because it’s too large. But we’re o.k.” Whew! Who knows what “too large” has to do with departures, but I’m glad we’re small. We took off in an easterly direction, banked to the south, then headed west. The sky was beautiful. Puffy cumulus clouds looked like marshmallows stacked in the sky. Below, an archipelago: I didn’t realize there were so many small islands of the coast of Florida. Miami is bathed in sun. Skyscrapers line the east coast, and there’s a lot of water in Miami itself. Who knows what it’s going to look like in 24 hours. Heading down to Dallas The pilot just announced arrival in ten minutes at Dallas. I’m packing up my computer. I’m tired. But believe it or not, it’s been a great trip. People “Me First” people At the gate where we got kicked off our September 7, 9:30 pm scheduled San Francisco departure flight, there were American Airlines (AA) attendants answering questions from people in their order in the line. Some people thought they deserved special treatment: they looked young and healthy to me, so neither age nor illness appeared to be an issue. But there they were pushing their way to the front. The AA people were firm: “we’re talking with people in the order they are in line.” One guy wouldn’t take no for an answer: he went to the other counter agent’s line, and pushed himself forward there. Same answer. A different answer might have precipitated a riot; I would have been a rioter! Same thing happened when the sheriff’s deputies arrived—the “me first” people trying to get ahead of the line. The Cops The five deputy sheriffs who showed up at our gate to make sure things didn’t get out of hand were interesting: three white guys and two black women. One of the white guys and one of the black women acted “tough cop”; the other black women was a humorist and actually fun to be around. (She’s one year from retirement, and looking forward to traveling, she told me. I asked her if she was in a union… “yes” … “which one”… “PBA” (Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association) …”what kind of pension plan do you have?”… “a good one: 75% of my best paid five years.”) One of the remaining white guys was a social worker: he really was helping people as best he could with not much more information available to him than any of us heathen passengers had. The last guy was the strong silent type. Just stood there looking kind of ominous with his arms crossed most of the time. I’m my brother’s and sister’s keeper people This was told to me by one of the women in today’s line, about her experience in the same line yesterday. An older man was desperately looking for his Alzheimer-ill wife who had wandered off while he was dealing with a ticket agent. A scouting party was pulled together, but turned out not to be needed. A young man encountered her at a gate where he had just won the lotto (a drawing of the few available seats for the 50-per-plane standby travelers. (Some people scheduled to be on planes couldn’t get to the airport or for some other reason were staying in Miami). He brought the missing-wife with him to the customer service counter. Somehow it turned out that if he sacrificed his ticket, the couple could get on a flight. I never did figure out how that worked, and maybe it was an airport legend already being born, or I got the details wrong. Anyway, it was a nice feel-good story. My hat created a brother’s keeper story as well: “Sir,” said one of my fellow Gate 37 line members, “you left your hat hanging on the rocking chair.” “Would you watch my suitcase for me?” “Of course.” I quickly returned to the counter area, got my hat and went back to the gate. I had my own feel-good story: after two hours in yesterday’s line, my 80-year old feet didn’t want to stand any more. I asked the young lady with the dog if she’d move my suitcase along while I found a place to sit for a while. “Of course,” she replied. Strong Suits Come Out In addition to the two people at the counter last night, AA had a roving agent who moved down the line to answer “quick questions”. Nobody had any of those, they all wanted his time. This guy was extraordinary, and obviously fit for his assignment. No story was too insignificant for his sympathy. No detail was too small for his attention. No complaint seemed without merit. And no matter what the story, the answer turned out to be the same: “There are no more seats; every plane has a wait-list; you won’t get any flight out of Dallas before Monday. Go to a shelter.” All said calmly and with a smile. He was made for the job. There were lots of people like that: flight attendants, ground crew, counter personnel, waiters and waitresses, hotel staff. A lot of people helped make the best of a bad situation. Today’s line at Customer Service (“Gate D-37” is now indelibly imprinted in my mind) was a totally different story from yesterday’s chaos, frustration and anger. One of the people in the line told me that there was a near-riot here late last night because of the snail’s pace of the line, due to the presence of only two agents at the counter. Today there were eight. And there were fewer people in line. And, lo and behold, when I got to the counter there was a seat—the one I’m now sitting in as we head to Dallas. Meanings Be persistent. Be skeptical. Hope for luck. Had I not returned to the customer service line for a fourth try, I would never have gotten on this flight. Beside my general ornery character trait that arises in these circumstances, I thought about institutional dynamics. AA didn’t want a repeat of the scandal in Chicago when a United staffer dragged a doctor, who turned out to be Chinese which added the dimension of race, from a plane—all on living cell phone video! Not very good for the bottom line! My thinking about that bottom line told me that by today the AA higher-ups who thought about profits and had a longer term view would have passed the word down: no egg on our faces! I think that’s why there were so many extra people at the ticket counter today, even with far fewer people in the line. And I had a little bit of luck! Race In the line today, I was between two Jamaican women who let me in their conversation. The younger of them was traveling with her older aunt who came to Miami for some medical treatment. Now they were having difficulty getting home. The older one was “going home” after a number of years living in either Georgia or Florida. “At home,” she said, “you can go anyplace on a bus or a jitney or in an inexpensive taxi or by foot. Here, everything is so far apart and it’s so hard to get from one place to another.” And the pace of life was better at home; and the people were friendlier. As the conversation went on, the older woman said, “Do you notice: almost all the people in the line are of darker skin; you don’t see fair-skinned people here.” “I’m pretty pale-faced,” I piped in. “I didn’t mean you,” she said. The younger one was skeptical. So was I. Then I looked at the line: of the 30-or-so people in it, I would estimate that at least 80% of them were black. Could this be? I still doubt it. But in today’s world, I could believe it, and surely I can understand how a black person would believe it. W.E.B. DuBois had it right: “…the world problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line…” Add the 21st. And don’t forget: he thought class was important too. Were he alive today, he’d add gender. Analysis Crippled programs syndrome When I worked as lead organizer for San Francisco’s Mission Coalition Organization in the late 1960s, our volunteer lawyer in our dealings with the Federal Government developed the “crippled programs syndrome” concept. It applied to the inadequacies of federal programs that were underfunded, constrained by limiting guidelines, and legislatively designed so they wouldn’t compete with the private sector. Then, when beneficiaries and the broader public complained about the programs, the conservative, anti-government crowd used the program inadequacies to argue that government doesn’t work. Remember Ronald Reagan’s, “government is not the solution; it is the problem”? Applied to the airport situation, I found some parallels:

Union contracts stipulate maximum hours for pilots to be in the cockpit—for very good safety reasons. Maybe the provision is also in flight attendant agreements as well—I don’t know. That turned out to be another reason for our plane heading back to the gate. “If we don’t leave in four minutes,” our pilot informed us, “we have to take you back to the gate because of contract provisions. We will have to be in the air too long.” “Give them an inch, and they’ll take a mile,” is the standard trade unionist’s response to a query about “a little flexibility”. There’s good reason for the argument. Add all this together, and you get the mess we had at the Miami Airport—a mess that would have been much worse had it not been for the spontaneous organization that took place among the people most adversely affected by what was going on. Is there a better way? The Airport Became a Community Trapped in the airport with nothing to do but deal with airlines and stress, and talk with others who were in the same boat as, you created a community—a group of people who shared intense and meaningful experiences, and who knew their interests were in some way connected with each other. In this community, boundaries created by race, class, language, nationality or anything else other than common plight faded into the background, opening space for relationships. Further, there were no hierarchies providing rules, regulations, guidelines, precedents or customs to tell us what we ought to do. Stress combined with an absence of rules to specifically define a situation brings out the best and worst in people. I saw dozens of airport workers stretch to make things work for beleaguered passengers: the waiter and manager at the Irish Pub did all they could to make me comfortable and get food to me for what I thought might be a several-day stay in the airport; for the most part counter people were infinitely patient with some customers who actually yelled at them, and all the passengers who were desperate for a way to fly when there wasn’t one; the pilot of my flight left his cockpit, came back to the economy section, and invited a man with his young son to take a look-see in the cockpit as we waited for stragglers to board the plane; a flight attendant who could have been home volunteered to work the shift to make things easier on passengers and fellow staffers; an electric jitney driver re-configured the luggage he was carrying so I could squeeze on his cart for the extra-long trip from one “D” gate to another. (Dallas Airport doesn’t have moving walkways; there’s a skyway that operates overhead, but I wasn’t sure it was working so walked most of the time.) The inventiveness, ingenuity, generosity and cooperation witnessed in the airport was partially possible because people were working outside their normal “rulebooks”. Relationships were peer-to-peer, horizontal in character rather than the typical hierarchy of status and power that governs most institutions, and that is governed by detailed rules. Could there be lessons here for a better way to organize things in society-at-large? Imagine the airport and airlines organized according to different principles and in different structures. First of all, workers, travelers, managers, airline hub communities, and other stakeholders would own airlines and their support services with widely shared stocks. That way the people who are on the ground interacting with travelers would be the ones making decisions—not a distant management interested in CEO salaries or absentee stockholders interested in the maximization of profits. Second, everybody would be organized: customers, workers, communities. They would all have the capacity to act on their particular interests so that the general interest/common welfare didn’t end up screwing anybody. Results are negotiated, not imposed. Third, site structures would have a great deal of autonomy to deal with both routine and extraordinary circumstances. Granted the exceptions noted above and yesterday, the overall impression I had was of workers who wanted to serve and do a good job, and travelers who were generous in spirit and caring about others who might be facing special circumstances that required special attention. The older Jamaican lady in today’s line put it clearly: there should be recognition of special circumstances like age, health, necessity of getting to one’s destination for important work or health reasons, and so on. Lots of wisdom in that idea, but it implies trust in good will rather than reliance on rules. It implies a basic decency on the part of people if they don’t think they’re being suckers. If they had authority, I think those with good will would impose their wisdom on the “Me-First” people. Bullies shrink when faced with opposition that is bigger than they are. One size fits all justice is better than the arbitrary and capricious behavior of a king, boss, landlord, administrator or anyone else who isn’t accountable to the people affected by the decisions. But not all people are in the same circumstance, and justice based on core principles but with flexibility to take into account mercy and individual circumstance might be even better. Lord of the Flies? When I was an undergraduate major in political science, we read William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies. A group of British youngsters, probably sixth graders, was stranded on an isolated island. They organized themselves for self-governance. It quickly declined into chaos. Authority was turned over to a dictator. The book draws its philosophical premises from Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, in which life is “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.” There is a “warre of every man against every man…every man is Enemy of every man…” In this circumstance, men give up their freedom to be ruled by a monarch who imposes order on the disorderly. Hobbes is a major philosopher in the history of conservatism. I have a different view. My experience at Miami International Airport confirms it. Most people behave toward one another with decency and generosity when they think that’s the rule of the day. Only when they think that’s the way suckers behave do they resort to “me first.” Hegemony? This is a “sidebar” to people who think most people are selfish, and think the country’s politics reflects their attitudes. It is commonplace among people seeking transformational social change to ascribe their failures to “hegemony”. Often citing Antonio Gramsci’s prison writings on the subject, they argue that the dominant system rules not only, or even predominantly, through its control of political and economic institutions, but primarily because it convinces the very people it exploits to consent to their subordination. According to this logic, the reason this or that cause is defeated is because people are “brainwashed” and believe in the dominant culture’s myths of rugged individualism: “me first”, “watch out for numero uno”, keep up with the Jones, you are what you consume, and a related set of pacifying ideas, “you can’t fight city hall”, “the system is too powerful to fight,” “one politician is no different from another”… Ideology in this case serves as a rationale for defeat: you don’t have to analyze your strategy and tactics, because you know in advance that you can’t win. Experience in the airport community that was my home for two days suggests something different: a majority of people believes they are their sister’s and brother’s keepers. Or, in secular terms, that there is a common good for which they have some responsibility. In the absence of opportunities to effectively act to further these values, most people set them aside. In what they see as the mainstream, the people who do act on them are saints, martyrs or suckers. The people in the long, slow line I first waited on let the London-headed woman ahead of them because they had a responsibility to do the right thing by her, and they were in a context—the airport community—that supported this action. The people who did a variety of little things to help others, things that often involved going beyond watching out for numero uno, were similarly acting for something larger than themselves. The support people provided, and are continuing to provide, for one another isn’t a secret either. CNN and the PBS News Hour are filled with stories of people coming together to act in solidarity with one another. The roots of these actions lie in the country’s small “d” democratic heritage, and the teachings of the world’s great religions that are shared by most Americans, whether born here, in Europe, in Africa, in Latin America or in the Middle East. I don’t know enough about Asian religious/cultural teachings in these areas, but I suspect these values are to be found there as well. In most settings the opportunities to act in the ways the airport community acted don’t exist. You can be a volunteer in a soup kitchen or as a docent in a museum, and you can give money to charities that assist the unfortunate, but the principal activities of your life have to do with securing the well-being of you and your family. Replicate The Airport! The challenge of our time is larger than any specific issue, no matter what its merits. If we cannot substitute community based on the values supported by the people in the airport, we will be in a continuing defensive battle against profiteers and power aggrandizers who define the world as a survival of the fittest and operate accordingly. What follows? To replicate what happened in the airport requires a renewal of the civil society voluntary associations that are the bearers of these values—churches, temples, synagogues, mosques and other communities of faith; unions; interest and identity groups. By renewal I mean the transformation of these organizations into places of ongoing participation by the members as distinct from places in which nominal members leave the work of the organization to a handful of paid leaders and staff and their coterie of volunteers. To replicate what happened in the airport requires multi-issue organizations. As African-American poet and feminist Audre Lord put it in “Learning from the 60s”, an address at Harvard, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” To replicate what happened in the airport demands continuing activity, not ad hoc demonstrations after which most people go home and resume their private lives; shared reflection on the meaning of what’s being done; internal member/participant education that places action in the continuing contest between the haves who want to keep and the have nots and have-a-little who want change, and; celebration that creates new heroes among everyday people and a new story of history being made by us as well as “big names”. That’s the organizing challenge for our time. If this challenge is met, the Donald Trumps of the country will fade into the dustbin of history. Postscript. As my flight was descending into the Dallas Airport, I opened American Way, the AA flight magazine. There I found “The people of Gander opened their homes to complete strangers,” by pilot Beverly Bass who on 9/11 (the infamous one) flew her re-routed plane into this small Newfoundland village. She writes, All told, about 7,000 passengers on the small Canadian town, nearly doubling its population…[T]he people on the ground were phenomenal They delivered everything you could imagine throughout the night to the planes—diapers, formula, nicotine patches. They even filled 2,000 prescriptions for people who had packed their medicine in their checked bags. When we got off the planes the next morning, tables of food lined the airport. The residents had stayed up all night cooking for us…Gander treated us like family, opening their homes and hearts. The flight crews stayed at hotels and schools, while the town converted churches and gyms into shelters for the passengers. When those filled, the people opened their homes to complete strangers and prepared thousands of meals for their guests. It’s now about 11:00. As luck would have it, my Dallas-SFO flight is delayed by more than an hour. I’m really running out of gas. I know I’ll sleep on the plane. If “the system” treats people like shit, they will feel like shit. If they feel like shit, they will treat other people like shit. Some people focus on changing the way the system treats people. In my terms, those people are advocates--people who speak in behalf of others who they think aren’t able to speak for themselves, or lack the power to speak for themselves. Some lawyers, union business agents, social workers, politicians and executive directors of advocacy organizations are among those in this category. Others are providers of services--people who offer something to alleviate feeling like shit or even making the shit go away. Some counselors, trainers, therapists, healers, affordable housing builders, inner-city teachers and child-care center workers are among those in this role. And other people challenge those who are being shit upon to organize themselves to act to change the shitty system and change the shitty circumstances in which they find themselves. That requires of the people being shit upon by the system that they take responsibility to change the way political, economic, social and/or cultural power are exercised. Since most of their efforts in trying to change the system have been rejected or otherwise unsuccessful (“you can’t fight city hall”), organizing them is difficult. The talent for doing it is rare; I don’t find it too often. The people with this talent are community, labor, interest and identity group organizers. I distinguish organizers from those who might occasionally get the shit-upon to show up for a march or demonstration but then return to their previous condition; I call these people mobilizers. The line separating organizers and mobilizers is fuzzier than I’m making it appear. Among advocates, service providers, mobilizers and organizers are some people who excuse the shitty behavior of shit-upon people who shit on others by pointing at the shitty conditions under which the shitters live. I think that’s both an intellectual error and a strategic mistake. Yet other people condemn the people shit on by the system for being shitty. They (accurately) say of these people that they possess choice. They omit, however, any understanding of what living in shit does to people. I think that’s a big intellectual error and a strategic mistake as well.* Shit-upon people of the world unite! You have nothing to lose but the shit in your lives. *An amendment was offered by one of the readers of this paragraph:

"[T]he people that condemn SOME of those shit on by the system for being shitty themselves to other people also being shitted on by the system, understand what living in shit does to people, but also understand that removing the shit from those shitted on people sometimes requires removing the shittiest people from their environments. The people that make this condemnation understand that the union of shitted on people of the world and their organization toward a system that is not shitty is what will make the world less shitty, BUT with the shittiest of the shitty being allowed to terrorize the shitted on, the shitted on will have to continue their focus on mere survival in shit, rather than on fixing the shit, or they might be killed by those shitty people. The shittiest of the shitty, just like those shitty people who benefit most from the shitty system simply don't care about the desire of those living in shit to not live in shit. Both of these shitty groups are obstacles to the shitted on not living in shit. One adds to the shit sneakily, the other adds to the shit in the open." In the recent (5/16/17) Los Angeles Unified School District—second largest district in the nation—Board election, pro-private charter/voucher candidates defeated the incumbent school board president and a candidate who shares his basic views. Some $14 million was spent, most of it by the winners—which will no doubt be the reason given by many for their victory. I think it is more complicated than that.

Here is a framework for understanding the Los Angeles school board election (a framework that I think is also applicable to Trump’s victory and other electoral results with which most readers of these comments are not pleased). The framework has three parts: (1) the crippled programs syndrome; (2) the erosion of civil society, and; (3) the failure of organized labor to be much more than another interest group, and of broadly-based, multi-issue, community organizing to reach what I think is its potential. 1. The crippled programs syndrome I wish I could claim this appellation as my own, but it comes from a paper with that title written in the early 1970s by Steven Waldhorn (a long-time friend of mine) when he was at Stanford University. The paper’s essential argument is that government programs for the poor are often inadequate because of crippling legislative, guideline and appropriations constraints imposed upon them at the outset by conservative legislators and administrators. Having crippled them, these conservatives then widely trumpet the failures of government programs. Inner-city schools are among the crippled programs. (Imagine the difference in outcomes if teacher salaries were doubled, classroom size halved, breakfast and lunch provided for all students, and program monies were abundantly available for things like the Algebra Project.) 2. The erosion of civil society This subject is at the core of what I do and think. We cannot have a vital democracy without vital, voluntary associations, democratically constituted and funded by their members. It is these groups that are the underpinning of democratic politics. Without them, politicians are dependent upon media to reach voters, and media costs lots of money which, as few would deny, makes those politicians increasingly dependent upon those who fund their campaigns. Without these associations there is nothing standing between individuals and families, on the one hand, and, on the other, mega-institutions like large corporations, government and large nonprofits (as in the health-care system). In the absence of these “mediating institutions”, everyday people are disconnected from civic life as citizens. Instead, they are “recipients” or “beneficiaries” of programs about which they have little voice. Their voicelessness makes them prey to demagogues who exploit it and promise to stand for “the people” against the mega-institutions that dominate society. (Note that this framework excludes from civil society the typical nonprofit which—whatever its merits, and they are often many—is part of the problem, not the solution. In the low- and moderate-income communities in which I worked during the years of the poverty program, model cities, and a number of other federal programs aimed at alleviating poverty, there emerged a plethora of “community-based non-profits”. In general, the purpose of each was good. And many of them did a good-to-excellent job implementing that purpose; others were simply part of a patronage machine. Whether excellent or worthless, their cumulative effect was to erode voluntary civic associations which had a “bottom-up” character and substitute for them the particular structure and character of most nonprofits: self-perpetuating boards of directors, no or non-voting membership, total dependency on external funding—all of which resulted in no participation and no community accountability.) Cumulatively, they are an example of the sum being less than its parts. 3. The labor “movement” and broadly-based community organizing When I was a boy, my parents did not miss voting in elections. Their guide to how they cast their ballot was the west coast longshoremen’s union slate card. The International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) was a Communist-influenced/left-wing union; it was expelled from the CIO during the post World War II red-scare period. My folks were part of that left-wing world. Even though not members of ILWU, they trusted it. They had personal relationships with members and leaders in it. They were part of a vibrant community in which politics was regularly discussed, social gatherings took place, educational activities were numerous, and action for social and economic justice was central. My parents voted for those slate card-recommended politicians no matter how much campaign money was spent by their opposition. That ILWU was part of the John L. Lewis-led Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and the CIO of the 1930s was part of a broad “progressive” movement that spoke for the common good and general welfare. Whatever its weaknesses, and they were surely there, these unions cared about more than the narrow, though important, workplace interests of their members. When Saul Alinsky organized Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC), one of its principal activities was to support a strike of the Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee (PWOC). And BYNC, whose members were for the most part eastern European “ethnics”, was an outspoken supporter of racial justice—for example, providing testimony for fair employment practices. Sad to say, most parents don’t see teacher unions as outspoken supporters for the education of their kids. And for good reason. If it were otherwise, the 25,000+ teachers (60,000+ total employees) in the LA School District would have been the base for a door-to-door/home visits/small house meetings face-to-face election campaign that would have convinced the number of voters needed to win: 31,000 for Zimmer, and 14,000 for Imelda Padilla (the union-supported, anti-voucher/private charter candidates). And nor would there have been a mere 11% (that’s not a typo!) voter turnout in the election. And that doesn’t even count unions with no direct relationship to public schools. The self-identified “labor movement” (which isn’t moving very much, and sometimes moves backward rather than forward) has become another “interest group”. Its word doesn’t mean much to the general electorate, and in some cases not even to its own membership. Broadly-based community organizing in what might broadly be defined as “the Alinsky tradition” is now almost 80 years old. The current veterans in the field have been engaged in the work for 50+ years. I count myself among them. For reasons that are beyond the scope of what I want to say here, we have not reached the people power capacity, nor broadly expressed the vision, that characterized the CIO at its best. Without substantial change in these two arenas, the present situation in the country is likely to persist. Electoral victories by even the most “progressive” of candidates are not sufficient to turn the country around; they don’t have the power to combat things like capital strikes that are likely to follow any significant efforts at reform. The Result Combined, these three factors—crippled programs syndrome, erosion of civil society, and failures and weaknesses of organized labor and community organizing—create the circumstances in which “neo-liberalism” is now the dominant ideology of the country (and the western world). While I think it rests on shaky foundations, this point of view is the underpinning of shrinking government (except for the security-military industry complex), charter schools and vouchers, market solutions to all human problems, rugged individualism and a consumer culture. The results are the present vast inequalities of income and wealth, the largely unrestrained power of corporate and Wall Street America, and growing hostility toward “The Other,” whomever she or he may be. Fortunately, a majority of Americans do not agree with significant parts of this ideology, and they want something different from their politicians than they are getting. In poll after poll, voters express views that are far more consistent with a notion of the public welfare and common good, as well as unity in diversity, than they are with “watch out for number one” or any of the “isms”. So I do not despair. But there sure is a lot of organizing work to be done. Of course we should resist Trump (and Obama and all those who preceded him) in their efforts to deport “illegals”, most of whom came to this country because U.S. negotiated “free trade” agreements eliminated their jobs or farms in their home country. How are we to do this in a way that goes beyond symbolic protest?

In what follows I want to briefly outline what I think will be the likely sequence of events to the present course of action that seems to have the full attention of the resist movement, and consider a different course, or at least an additional course, that might have a different outcome. Non-Cooperation and the Likely Trump Response Across the country local, and now state, governments are adopting policies to refuse cooperation with ICE. In response, the Trump Administration is rattling swords and threatening dire consequences, the most likely of which will be cutting of federal funds to state and local governments that don’t back down from their non-cooperation positions. Will Trump follow through? There is little reason to think he won’t. Will court challenges to what Trump does stick? Even if upheld in District and Circuit courts, there is little reason to think they will when they reach the Supreme Court new majority with Trump nominee Neil Gorsuch. If I am right in that appraisal, who will get hurt when funds are cut? For the most part, poor people, and those public employees whose salaries are paid by the grants that will no longer be. Here’s the dilemma: if it were their decision to take the cuts—as, for example, it is the decision of workers who vote to strike to forego their wages and risk their jobs—that would be one thing. But it’s not. Those who are hurt are not those taking the action. The local and state governments responsible for the loss of their programs and jobs are likely to fold under this pressure. And the argument against folding is not all that strong. We are talking about national policy. There is just so much that state and local governments can do to buck it. Even the once powerful Dixiecrats finally had to crumble in the face of federal intervention against legally-sanctioned racial discrimination in the south. Further, if these governments don’t fold they are asking very vulnerable people to make a sacrifice in whose decision they played no part. Could these governments make up the loss in revenues? Maybe. It would probably require adoption of new taxes, which would have to be substantial to compensate for hundreds of millions of lost federal income. Will they do it? And even more pertinent, will they do it with “progressive” rather than “regressive” tax measures? None of them have adopted in any substantial way that kind of tax reform thus far. Conclusion: the end game doesn’t look very good in the present scenario. Divide and Conquer From the Bottom Up: An Alternative Or At Least A Complementary Strategy? Our side cannot win this fight or, for that matter, any major fight in the national political arena at the present time, and the picture isn’t a lot different in the states. The cards are stacked against us: conservative Republicans control all three branches of the federal government, as well as a majority of state houses where they are using their authority to devise ingenious measures to limit the franchise for historically Democratic Party voters—particularly African-Americans. If we don’t have a direct shot at the corner pocket, is there bank shot on the table? (Or, if you don’t know pool, are there other targets?) I think the possibility for those lies in the corporate sector, in particular in businesses or business associations that were public supporters of Trump, in general, and of his immigration policy, in particular. What would be done in relation to such businesses? Call upon them to publicly demand that the Administration back off its family-breaking policy. What if they won’t go along? Boycott their products and/or services, and use non-violent direct action tactics to publicly shame their executive officers. (A symbolic “don’t buy” day might be used to supplement the “don’t work” day that is now to be engaged in on May 1 by immigrant workers and their allies.) Could this work? I don’t know. Neither does anyone. But in the 1960s and 1970s when boycott activity seriously damaged the profits of California agribusiness, growers suddenly became friends of collective bargaining legislation. (Up to that time, farm workers were able to engage in secondary boycotts because New Deal legislation creating the national collective bargaining framework excluded them—the direct result of the Dixiecrats who were protecting the near-slave status of southern black plantation workers. But 30 years later, in California, the shoe was on the other foot. Governor Jerry Brown got an excellent collective bargaining law passed by the legislature. (In fact, Cesar Chavez, leader of the United Farm Workers of America, initially opposed legislation. He had the power, via national boycotts, to directly force growers to the bargaining table; he didn’t want to give it up to a third party. History proved him right when a newly elected Republican governor appointed pro-grower votes to the Commission that implemented the law.) If profits are the leverage, then a whole new set of demands on government is possible. Local and state governments or substantial purchasers of all kinds of goods and services from the private sector; they are depositors in banks; they invest in pension funds; they subsidize various businesses. More research would no doubt uncover more levers. A General Point On a broader front, I think those who are now fighting defensive battles over affordable housing, budget cuts in social programs, job losses to offshoring and similar issues should consider direct action aimed at corporate targets—not symbolic action, like picketing a building where a corporation is located—but action that hurts the bottom line. To do that will require mobilizing on a level not yet reached by most protest action. Those who consider themselves the organizers of thee actions need to look at how to add a zero to their numbers. Government in the present time is not a likely arena for victories. Perhaps head-on confrontation with business is. Preface

Dr. Carol Anderson is a professor of African American history at Emory University. She was recently awarded the National Critics Circle Award for her book White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. This is a brief commentary on Pamela Newkirk’s review* of Anderson’s White Rage, and on her 2014 Washington Post op ed article, “Ferguson isn’t about black rage against cops. It’s white rage against progress,”** which was the forerunner of her book. I haven’t yet read Carol Anderson’s book, only the review of it and her article that led to the book. All her facts about what happened to African-Americans in the United States seem right to me. But I also think there is a serious problem with her interpretative framework. The latter is what I address here. Undifferentiated White People “Rage,” “resentment”, “fear” and even “anger” seem to me unusual words to describe the conscious and deliberate efforts by powerful “white” people, and their coopted allies of a variety of other colors, to keep what they have: power, status, wealth and income. As Anderson puts it in her Washington Post column that led to White Rage, “the real rage smolders in meetings where officials redraw precincts to dilute African American voting strength or seek to slash the government payrolls that have long served as sources of black employment,” and “…white rage doesn’t have to take to the streets…to be heard.” She could have added bankers who draw red lines that determine who gets what loans at what interest rate (or doesn’t get them at all). Or school administrators who fail to adopt policies and practices that don't track bottom quartile kids into dead-end jobs or prison. Her words are more accurate when applied to her post-Brown v. Board description: “But black children, hungry for quality education, ran headlong into more white rage. Bricks and mobs at school doors were only the most obvious signs.” Isn’t there an important difference between the angry demonstrators who sought to block black student entry to Little Rock’s Central High School and the white plantation owners who sought to reclaim their power after the Civil War, the white politicians who want to keep the power they have, or the white bankers whose decisions destroyed more than half the wealth of the country’s black and Latino communities? More on that question in a moment. Pamela Newkirk, The Washington Post reviewer, of Anderson’s book accepts the framework Anderson presents, and adds “rebellion” and “revolt” to its language: “Anderson, a professor of African American history at Emory University, traces the thread of white rebellion from anti-emancipation revolts through post-Reconstruction racial terror and the enactment of Black Codes and peonage, to the extraordinary legal and extralegal efforts by Southern officials to block African Americans from fleeing repression during the Great Migration. She continues connecting the dots to contemporary legislative and judicial actions across the country that have disproportionately criminalized blacks and suppressed their voting rights.” Elite Power The old Confederacy’s institutional/economic back was never broken: the plantation owners retained ownership of their land. Forty acres and a mule was an unkept promise. When 1877’s great compromise took place, the political revolution that might have taken place was betrayed. The power of the oligarchy re-asserted itself. The destruction of the nascent alliance of freed slaves, African-Americans who were Freedmen, and white yeomen farmers who choose to become Republicans is detailed in the book, The Union League Movement in the Deep South, by Michael W. Fitzgerald. Read it and weep. But please read it. In more recent times, Democrats haven’t been any better when it comes to the scandal of what the banking industry did to minority community wealth. And Obama was part of it. Indeed, in Chicago he was part of the community development corporation-banks-builders-local politicians complex that undermined independent black community organizing that had been going on there. Like most of the black clergy, he was, indeed, complicit in it. Ditto on another scandal: his appointment of Arne Duncan as Secretary of Education. Newkirk quotes Anderson, “The GOP, 'trapped between a demographically declining support base and an ideological straitjacket...reached for a tried and true weapon: disfranchisement'." Both of them should include as part of the problem those black politicians who drew 80% black-voter districts to make their re-election a certainty. Absent from Newkirk, and, I suspect, Anderson, is any critique of the Democrats whose policies, including those of Obama, contributed to the rage of white working class people and to the disengagement from the 2016 election when minorities stayed home in droves—even in states where there was no voter suppression. Divide and Conquer from Below Also absent in this framework is anything to explain why the Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and other Rust-Belt state white ethnic Democrats voted TWICE for Obama before voting for Trump. To explain that requires adding mainstream Democrats, including Obama, but not for the reason of his being black, to the source of their rage. As long as these two groups—white elites and white working class—are treated as indistinguishable, there is little hope to divide them—which is what people who want racial and economic justice have to do. (To download the full text of this blog: "A Review of Fred B. Glass, From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement." Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.)